Digital Edition

Subscribe

Get an all ACCESS PASS to the News and your Digital Edition with an online subscription

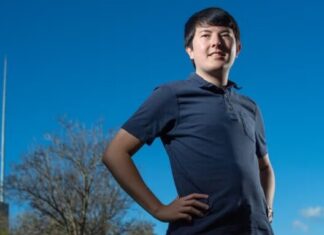

UniSQ researchers find potentially habitable planet 150 light-years away

Researchers at the University of Southern Queensland (UniSQ) have discovered a potentially habitable planet 150 light-years away, similar in size to Earth and with...